The Bassanda

Corresponding Society

Being a collection of archival & more recent material on the topic of Bassanda's history, culture, and musical folklore, from a variety of sources and learned correspondents. Post queries & commentary to the Friends of Bassanda Corresponding Society here

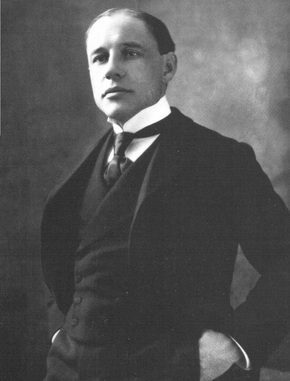

President emeritus:Dr Homer St John, PhD, DD (Kcing's College); Yezget Nas1lsiniz Chair of Oriental and Musical Studies, Miskatonic U.

Correspondents:

The Right Reverend R.E.C. Thompson, DD, Colonel, Army of the Confederacy (ret.)

The General, BM/MM, Music and Oriental Studies, General, U.S. Army (ret.)

S. Jefferson Winesap, secretary to the Society

President emeritus:Dr Homer St John, PhD, DD (Kcing's College); Yezget Nas1lsiniz Chair of Oriental and Musical Studies, Miskatonic U.

Correspondents:

The Right Reverend R.E.C. Thompson, DD, Colonel, Army of the Confederacy (ret.)

The General, BM/MM, Music and Oriental Studies, General, U.S. Army (ret.)

S. Jefferson Winesap, secretary to the Society

More from Bassanda: The Janissary Stomp

Collection of Bassandan folkloric styles, from the archives of Radio Free Bassanda: link

Table of Contents

- Alexei Andreevitch Boyar (1922-2010)

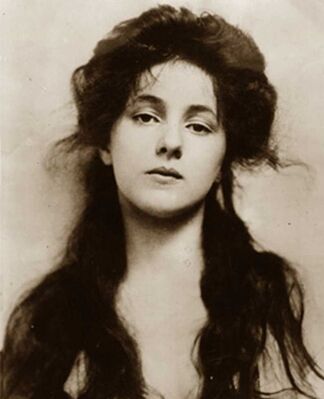

- Algeria Main-Smith (1862-1947)

- Anthea Habjar-Lawrence (1892-1961)

- Anthea Habjar-Lawrence’s “Ant”

- From the Bassandevalayana: Bassanda's traditional Myth of Creation

- Bassanda as historical role-playing game – and as education

- Bassanda as immersive theatre – and as education

- Bassanda's contingent possibilities for joy

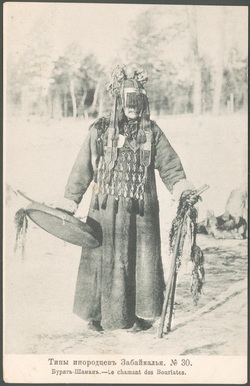

- Bassandan shamanic chant

- Brauḍasakī’s Bukasa: A Rare and Treasured Volumes Emporium

- Bronislava Nijinska (1890-1972)

- Buffalo Soldiers of Bassanda

- Celebrating Bassanda's National Independence Day

- Cécile Lapin (1882-1974)

- Celeste Roullet (c1890-1948?)

- Col. Thompson's Golden Era Rio Grande Gorge Rides

- Closing and Opening the Rio Grande Rift Portal

- Cold War agit-rock: Eliektryčnyja Drevy

- Colonel Thompson and the US Secret Service (NM territory)

- Colonel Thompson on Habjar-Lawrence Nas1lsinez

- Costume, persona, and paint

- Cultural Diplomacy and The “State Folkloric” Ensemble

- Dr St-John encounters spam

- The Eagles' Heart Daughters

- EHO Casting Out Serpents

- Etsy at Golden Gate Park, 1967

- From the Bibliotheque to Bassanda: Recruiting with the Colonel and the General, Paris 1906

- From the Matthiaskloster Grimoire

- Frontiers of Imperial Conquest and Exchange: the Case of Bassanda

- Going to See the Professor (Paris 1906)

- HM S. Owsley-Smythe of Throbshire Isle

- Homer St John & the BBC

- The International Society for Bassanda Studies

- James Lincoln Habjar-Lawrence (1859-1922)

- Jefferson Washington Habjar-Lawrence (1888-?)

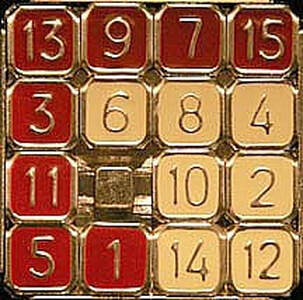

- King of the Hill for Bassanda market

- Lafcadio Hearn meets the Colonel

- Matthias's Mountain Rest Lodge

- A Meeting at the Museum

- Mid-winter hospitality and the cycle of the seasons

- Newly unearthed documentation re/ Bassandan FILM

- Notes on Bassandan ethnography

- On the Mountains' Peak

- Pappy Lilt (1871-?)

- Scattered in c1900 North America

- Pedlars, patent medicines, and “sono-pictographs”

- Seymour M. Queep reports upon findings in the New Mexico State Archives

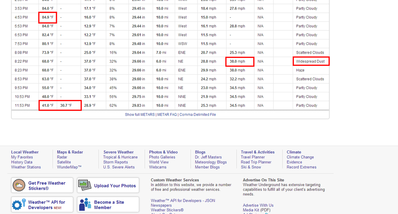

- Sixty Degree Temperature Drop

- Socialist Realism and the People’s Liberation Orchestra c1943-47

- Taking The Hippie Trail to Bassanda

- Testimony of Leon Avventoros Anderson, former OSS / CIA analyst

- The Bassanda Young Men's Pennyfarthing Expedition Club

- The Buddhist History of the Bassandayana

- The Charlatans and the time-traveling BNRO

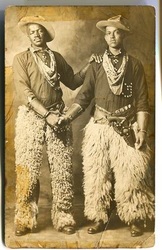

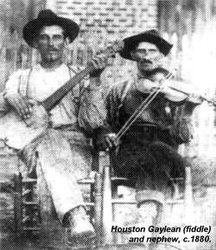

- The Colonel and Sam, archival photograph & accompanying accession information

- The Colonel and the Beast, Taos, c1955

- The Eagle’s Heart Sisters

- The Electromagnetic Trio (Dallas, c1925)

- The General Explains

- The Great Southwestern Desert post-Apocalyptic 'Sand Pirates' Band

- The Habjar-Sonic pickups

- The Kráľa Family Band

- The Lawrence Clan and the Ivy League

- The Legend of the Five

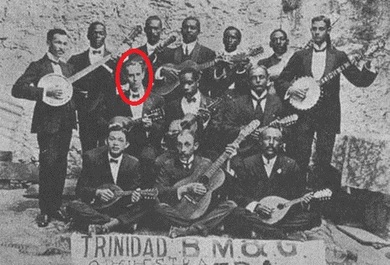

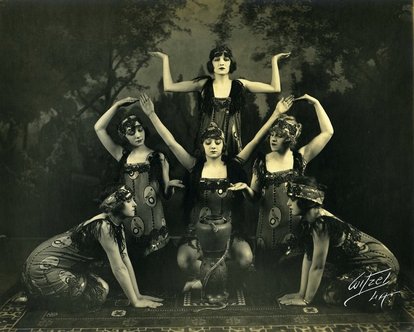

- The 1912 New Orleans Creole “Voodoo” Band a/k/a “The Ghost Band”

- The 1928 "Carnivale Incognito" Band

- The c1934 Intergalactic Pandemic Popular Front Band

- The 1936 International Brigade Libertarias Band

- The 1942 Casablanca Band

- The 1948-49 Berlin Air Lift Noir Band

- The 1965 Newport Folk Festival Band

- The Mysterious 1885 Victorian "Steampunk" Band

- The 1967 Rift Portal Accident

- The Return from the Rift, Part 1

- The Return from the Rift, Part 2

- The Royal Bassanda Bicycle Corps

- The St. Grydzina Correctional Institute Afternoon Drill Team

- The story of Binyamin & Meyodija

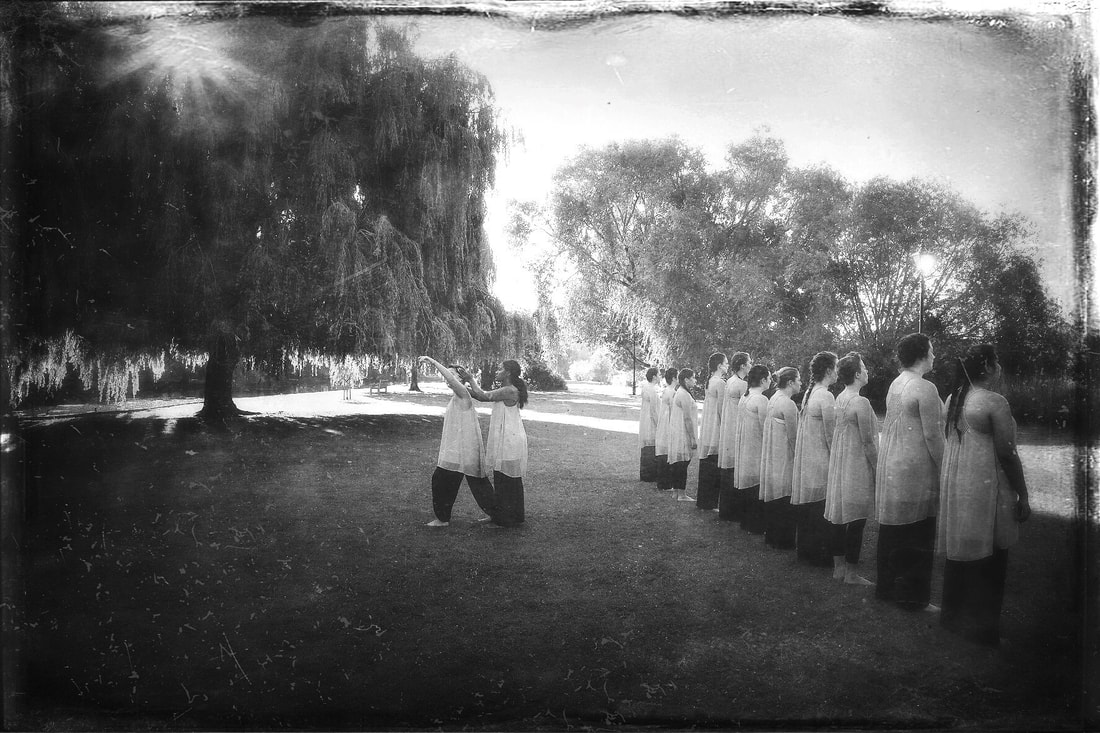

- The Taklif of Fifteen (Taklif 'ana al-raqasat): Bedfordshire, 1959

- The Thirteen Wise Companions: Bedfordshire, 1957

- The Tin-Pot Dictator

- Vassily Uel’s Ainḍarsa-kō-chōrā

- Why write the Bassanda universe?

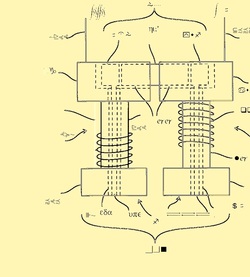

- William Cruickshank and the electrical traditions of Bassanda

- Winesap re-opens the Bassanda Question

- Xlbt Op. 16 premiere

S. Jefferson Winesap’s entry on the ESO for the revised virtual version of Nicolas Slonimsky’s Lexicon of Further Musical Invective

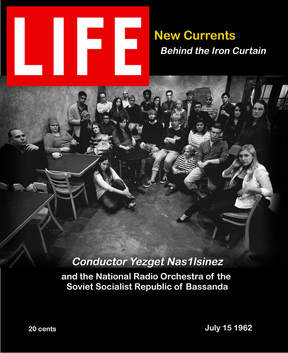

The Elegant Savages Orchestra arose from the ashes of the Soviet Era Bassanda National Radio Orchestra. Founded by Yezget Nasilsinez some time in the late 1940s, when Bassanda National Radio first went on air with funds from the State Directorate, the BNRO drew its personnel from all over Bassanda, in addition to various adventurous expatriate musicians from the West. Until the 1930s, when the Central Committee finally brought all regions of the mountainous interior and rocky coast under state political control, Bassanda had been the home of a wealth of highly regionalized and distinctive music, dance, and song traditions.

Recognizing that centralization of state communications risked the erosion of regional styles and resulting “cultural grey-out,” Nasilsinez, who came from a family of traditional bards but who had also trained in Paris in the ‘20s with Boulanger, and had been an early informant of John Lomax senior, argued passionately for the recognition and protection of these local traditions, both through an ambitious though underfunded field-recording program and through the foundation of a state ensemble showcasing these idioms.

The BNRO board and programming committee were the site of ongoing, sometimes contentious debates between Nasilsinez, who fought for the integrity and inclusive presentation of the regional idioms, including those which came from Bassanda’s often-persecuted ethnic minorities, and state commissars, who insisted that the Orchestra must present a unified, “sophisticated” and culturally-competitive face of the Nation to the rest of the world.

By the late 1980s, with the growth of glasnost and perestroika, and the example of the Bulgarian and Cossack state ensembles before them, the very elderly Nasilsinez and his musicians’ leadership committee made the decision to divest of the last vestiges of state funding and control, and go into exile in the West. They began a peripatetic “never-ending tour” of the rest of the world, as a cooperative and collective enterprise, under the name of The “Elegant Savages Orchestra” (the new title was a paraphrase of a possibly-apocryphal quote from one of Nasilsinez’s anonymous musical sources, who, upon hearing his lyrical description of the BNRO’s mission and plan, commented sardonically “well, yer a foine buncha elegant savages, are ye not?”).

Over time, the personnel evolved as elder musicians retired or deceased, but the ESO’s core principles, as envisioned Nasilsinez and evolved and carried forward by his musical lineage and the musicians’ cooperative committee, continued:

‘fierce dedication to the traditions and to one another.’

Recognizing that centralization of state communications risked the erosion of regional styles and resulting “cultural grey-out,” Nasilsinez, who came from a family of traditional bards but who had also trained in Paris in the ‘20s with Boulanger, and had been an early informant of John Lomax senior, argued passionately for the recognition and protection of these local traditions, both through an ambitious though underfunded field-recording program and through the foundation of a state ensemble showcasing these idioms.

The BNRO board and programming committee were the site of ongoing, sometimes contentious debates between Nasilsinez, who fought for the integrity and inclusive presentation of the regional idioms, including those which came from Bassanda’s often-persecuted ethnic minorities, and state commissars, who insisted that the Orchestra must present a unified, “sophisticated” and culturally-competitive face of the Nation to the rest of the world.

By the late 1980s, with the growth of glasnost and perestroika, and the example of the Bulgarian and Cossack state ensembles before them, the very elderly Nasilsinez and his musicians’ leadership committee made the decision to divest of the last vestiges of state funding and control, and go into exile in the West. They began a peripatetic “never-ending tour” of the rest of the world, as a cooperative and collective enterprise, under the name of The “Elegant Savages Orchestra” (the new title was a paraphrase of a possibly-apocryphal quote from one of Nasilsinez’s anonymous musical sources, who, upon hearing his lyrical description of the BNRO’s mission and plan, commented sardonically “well, yer a foine buncha elegant savages, are ye not?”).

Over time, the personnel evolved as elder musicians retired or deceased, but the ESO’s core principles, as envisioned Nasilsinez and evolved and carried forward by his musical lineage and the musicians’ cooperative committee, continued:

‘fierce dedication to the traditions and to one another.’

Reply from the Rev. Col. R.E.C. Thompson, LLD, Army of the Confederacy (ret.)

[in response to initial query from Dr Coyote]

The Rev. Col. writes:

4.30.13

Dr. Chris!

Funny you should bring this up just now... I've been doing some studies on-line and I serendipitously bumped into original research by Homer St. John and S. Jefferson Winesap (editors and publishers of the ground-breaking Yoknapatawpha Howlsman's Quarterly) at Five Tribes University in northern Mississippi.

Apparently, some time around 1879, eccentric, disgraced, and exiled Duke HM S. Owsley-Smythe of Throbshire Isle (which is as you know a tiny island lying at a point of almost perfect triangulation between Ulster, Scotland, and Baja California, the ancestral seat of which sits at Droole-On-Xthlan) travelled (as was the fashion of the times) to the nether reaches of the far east to study with so-called "ascended masters," at least one of which claimed to be able to transform his human shape into that of a small, spotted dog, which sometimes wore a fez and spoke in plain English. Owsley-Smythe was exposed to ancient texts describing the more arcane aspects of distillation, bookbinding, and - most pertinent to your essay - the construction of musical instruments.

It is not known exactly when Owsley-Smythe returned home (where in addition to his many other hobbies and diversions he attempted to create, as he wrote, "...a respectable Highland Scotch, nice and peaty, but using Agave and the heart of the Peyote cactus and filtered through - of all things - the most delicate films of mummy wrappings...") but it is almost certain that after his lengthy eastern tenure of possibly more than a decade, he met on his way home Madame Blavatsky, Rasputin, and - again, most pertinent to your essay - Yezget Nasilsinez's grandfather (or father - the records are not clear) Habjar-Lawrence Nasilsinez.

Diaries of Owsley-Smythe clearly show that he spent several weeks in the company of Habjar-Lawrence Nasilsinez at his great house in Irkutsk. Given the love of music that Habjar-Lawrence passed on to his grandson (or son) it is almost certain that he and Owsley-Smythe discussed the manufacture of musical instruments. It is further almost certain that Owlsey-Smythe passed through Bassanda at some point in his travels; perhaps even personally escorted by Habjar-Lawrence.

Owlsey-Smythe sailed from an unknown port on the Baltic to Boston and from there travelled by train back home to the Baja coast where he took the ferry home to Throbshire. However, he detoured on his homeward journey to northern New Mexico, and there came into contact with one General L., Esq. and one C. Thompson, Esq., who based on scanty clippings from territorial newspapers were veterans of the American Civil War (from opposite sides, the General fought for the Union, Thompson the Confederacy) who became fast friends in their mutual disillusionment with the war and "...flight from the insanity of the eastern establishment..." as Thompson apparently once wrote. There is in the archives of ethnographic collection at Miskatonic University a single faded photograph of HM Owsley-Smythe with the General and Thompson as well as some others which is labelled "The Young Gentleman's Oriental Society of Talpa, New Mexico: ca. 1892. The most interesting aspect of this photograph is that the General is holding what under high magnification appears to be Turkish saz, but one with distinctively Bassandan architecture and appointments! It could be possible that the instrument belonged to Owsley-Smythe or that he constructed it after his eastern studies and gave it to the General . The saz is rumored to be in a private collection in California, but so far its exact location is unknown.

Connections, connections! You never know what this kind of synchronistic research will turn up. Those desperate gentlemen St. John and Winesap should probably be in an asylum instead of co-heading the department of a major university! Let's stay in touch about this... I have little doubt that given their researches Five Tribes U. would be thrilled to host the Elegant Savages Orchestra. I'll do some digging here in New Mexico and see if I can find any remnants of the "Young Gentleman's Oriental Society..." If they have any archives... my God! What I might find!

Yours, The Right Rev. Col. C.

The Rev. Col. writes:

4.30.13

Dr. Chris!

Funny you should bring this up just now... I've been doing some studies on-line and I serendipitously bumped into original research by Homer St. John and S. Jefferson Winesap (editors and publishers of the ground-breaking Yoknapatawpha Howlsman's Quarterly) at Five Tribes University in northern Mississippi.

Apparently, some time around 1879, eccentric, disgraced, and exiled Duke HM S. Owsley-Smythe of Throbshire Isle (which is as you know a tiny island lying at a point of almost perfect triangulation between Ulster, Scotland, and Baja California, the ancestral seat of which sits at Droole-On-Xthlan) travelled (as was the fashion of the times) to the nether reaches of the far east to study with so-called "ascended masters," at least one of which claimed to be able to transform his human shape into that of a small, spotted dog, which sometimes wore a fez and spoke in plain English. Owsley-Smythe was exposed to ancient texts describing the more arcane aspects of distillation, bookbinding, and - most pertinent to your essay - the construction of musical instruments.

It is not known exactly when Owsley-Smythe returned home (where in addition to his many other hobbies and diversions he attempted to create, as he wrote, "...a respectable Highland Scotch, nice and peaty, but using Agave and the heart of the Peyote cactus and filtered through - of all things - the most delicate films of mummy wrappings...") but it is almost certain that after his lengthy eastern tenure of possibly more than a decade, he met on his way home Madame Blavatsky, Rasputin, and - again, most pertinent to your essay - Yezget Nasilsinez's grandfather (or father - the records are not clear) Habjar-Lawrence Nasilsinez.

Diaries of Owsley-Smythe clearly show that he spent several weeks in the company of Habjar-Lawrence Nasilsinez at his great house in Irkutsk. Given the love of music that Habjar-Lawrence passed on to his grandson (or son) it is almost certain that he and Owsley-Smythe discussed the manufacture of musical instruments. It is further almost certain that Owlsey-Smythe passed through Bassanda at some point in his travels; perhaps even personally escorted by Habjar-Lawrence.

Owlsey-Smythe sailed from an unknown port on the Baltic to Boston and from there travelled by train back home to the Baja coast where he took the ferry home to Throbshire. However, he detoured on his homeward journey to northern New Mexico, and there came into contact with one General L., Esq. and one C. Thompson, Esq., who based on scanty clippings from territorial newspapers were veterans of the American Civil War (from opposite sides, the General fought for the Union, Thompson the Confederacy) who became fast friends in their mutual disillusionment with the war and "...flight from the insanity of the eastern establishment..." as Thompson apparently once wrote. There is in the archives of ethnographic collection at Miskatonic University a single faded photograph of HM Owsley-Smythe with the General and Thompson as well as some others which is labelled "The Young Gentleman's Oriental Society of Talpa, New Mexico: ca. 1892. The most interesting aspect of this photograph is that the General is holding what under high magnification appears to be Turkish saz, but one with distinctively Bassandan architecture and appointments! It could be possible that the instrument belonged to Owsley-Smythe or that he constructed it after his eastern studies and gave it to the General . The saz is rumored to be in a private collection in California, but so far its exact location is unknown.

Connections, connections! You never know what this kind of synchronistic research will turn up. Those desperate gentlemen St. John and Winesap should probably be in an asylum instead of co-heading the department of a major university! Let's stay in touch about this... I have little doubt that given their researches Five Tribes U. would be thrilled to host the Elegant Savages Orchestra. I'll do some digging here in New Mexico and see if I can find any remnants of the "Young Gentleman's Oriental Society..." If they have any archives... my God! What I might find!

Yours, The Right Rev. Col. C.

Winesap responds

Colonel: There's simply no telling. In the 21st century, the material from the Bassanda Soviet Central Committee's archives (c1926-84) has become available, but it is heavily redacted. ESO founding director Nasilsinez was effusive in his advocacy on behalf of Bassandan regional and ethnic vernacular autonomies, but very reticent about his grandfather Habjar-Lawrence's Tsarist associations. Curiously enough, there are recollections of Nasilsinez, and his complex associations in post-WWI Paris, in the memoirs (unpublished) and tour diaries of the Studio der Fruehen Musik, which ensemble at the behest of vocalist Andrea von Rahm appears to have made sub rosa field trips to Bassanda during the early 1960s Brezhnev era. It is thought that these field trips may have yielded the stylistic influences which, in the period, sometimes caused Anglophile medieval specialists to refer to the Studio as "Radio Bassanda". Thomas Binkley, founder of the Studio, appears to have known Nasilsinez comparatively well, and the ESO's first, early 1980s tours in the West appear to have been based upon touring networks and contacts pioneered by the Studio 20 years before.

The Colonel replies...

R. Smythe-Hinde's connection to all this is unknown, St. John told me. From his name, it seems possible that he's a relation of HM S. Owlsey-Smythe, but it might also be just more weird synchronicity. You know that R. Smythe-Hinde's father studied in Southern Italy when A. Crowley had his "abbey at Thelema" in Palermo around 1922, and Crowley had also spent almost a year in Mexico "... trying to make his image in a mirror disappear..." so he might have had contact with an elderly Owsley-Smythe as well. There might be a causal chain between the Sr. Smyth-Hinde, Crowley, and Owsley-Smythe, but at this point, who knows? St. John can't even figure it out, and it seems unlikely as best that an archive of New Mexican musical occultism should end up in a New England University. Except that... rumor has it that both some of Habjar-Lawrence Nasilsinez's papers are at Miskatonic, as well as some of the arcane books that Owsley-Smythe studied in the far east with the ascended masters! Jung would have a heart attack...

C.

C.

To: The Right Reverend R.E.C. Thompson, DDS, Colonel, Army of the Confederacy (ret.)From: S. Jefferson Winesap, graduate student in music, ethnology and cultural alternatives, Miskatonic School of Oriental and Musical Studies, for Professor St. John

Re: The Bassanda Corresponding Society

Date: 2 May 2013

Re: The Bassanda Corresponding Society

Date: 2 May 2013

Dear colleague:

It has occurred to us (myself and Professor St. John, who represent the small but dedicated curatorial staff of the Bassanda archives-in-exile at Miskatonic University) that, with the advent of the new millennium and its remarkable communications tools—what would Yezget Nasilsinez have been able to accomplish with Web 2.0 and social media: the mind reels!—that the time might be right for a reinvestigation and reinvestment in public advocacy on behalf of the lost world of Bassanda. With the unexpected but very welcome interest shown, across a wide diversity of clienteles, in the activities and possibilities of the Elegant Savages Orchestra—who in exile on the Never-Ending Tour, continue, as you know, under Nasilsinez’s motto “fierce dedication to the traditions, and to one another”—we think that there is a distinct window of opportunity here. Though the massive gaps in the Bassandan historical and archival record resulting from the redactions and cultural reawakenings of the Soviet era can never be entirely filled, it does seem possible that, through the pooling of resources and insights from contributors around the globe, a remarkable amount of data might be collated and disseminated. We envision a “Bassanda Corresponding Society,” admission to which would be on the basis of invitation and special aptitudes, and which, through the magic of the social media which could never have been imagined by the first generation of Bassandan scholars (I am thinking here for example of the c1890s Young Gentleman’s Oriental Society of Talpa), could assist in recovery and new appreciation of our beloved homeland’s culturally and musically diverse riches.

This moment of opportunity as represented by social media and new technology, and by the interest in the ESO, is further enhanced by the presence now, here at Miskatonic, of a remarkably visionary yet practical Dean of Oriental and Musical Studies, who has pledged and demonstrated commitment to artistic inclusivity to a degree that the Professor and I (who remember the bad old days of previous administrations—and as you recall I have been a graduate student here, with the Professor as my supervisor, for nearly three decades) find almost unnervingly positive. In point of fact, that level of support, both financial (modest) and philosophical (vast), and the presence of a pool of enthusiastic students too young to have ever heard, or heard of, Bassandan music, has led the Professor and myself to conclude that we would be remiss in our debt to all that Bassandan culture, and our revered founder Baba Yezget Nasilsinez, gave us, if we were to decline this opportunity.

Colonel Thompson, please do be advised that the Professor and I recognize that your myriad obligations to extended family in the Mountains of New Mexico, and (forgive my mentioning a painful subject) the physical infirmities that have plagued you ever since the War, make it difficult or arduous for you to undertake travel. But we have had communications from Correspondents in Kansas City’s Fair Missouri Command, and from a Buddhist monastery north of you in Colorado, and even from the riverine environment of the Cincinnati river landings, which suggest that all memory of Bassanda is not lost, and that, in a wounded and suffering modern mass-media world, the message of Bassandan musical, cultural, and ethnic inclusivity may resonate more powerfully than ever.

Moreover, though no one could ever have predicted it, the General (B.M., M.M., Oriental and Musical Studies) has proven to be an absolutely exemplary “mature” student since his return to Miskatonic’s ivied halls, yet his tenure here is gradually drawing to a close.[1] We will be very sorry to see him depart, as he has provided such invaluable service to Miskatonic’s department of Musicology, Ethnology, and Cultural Alternatives, but we do feel an obligation as a result to take maximum advantage of his remaining time here.

That being the case, the Professor has directed that I inquire of you on two fronts: first, would your familial obligations and (again, forgive me) physical constraints permit your attendance and participation, in person, at a concert of Bassandan and related music, some time in January of the next year? The General , the Professor, and I all agree that your presence would provide an enormous inspiration and authentication to the young and developing musicians who are the next generation of ESO personnel. We do hope you will take this under consideration.

Secondly, and more immediately: would you believe it might be possible for us here at Miskatonic to take advantage of these new 21st century communications technologies, to author and host a “Bassanda Correspondences” section on the ESO’s website? As you’ll recall, Baba Yezget always believed that both technology, communications, and even modern bureaucratic/administrative structures could, in the right hands, yield personal, humane, imaginative, and creatively inspiring results. And, as I have said, there appears to be a network, largely incommunicado, of Bassanda friends and scholars in locations heretofore unknown or unidentified, with whom contact and collaboration might be initiated.

Do let us know your thoughts.

We remain, Sir,

Most respectfully,

Professor Homer St. John, PhD/LLD, etc., etc

S. Jefferson Winesap (graduate student in music, ethnology, and cultural alternatives)

Miskatonic U

CC: The General, BM/MM, Music and Oriental Studies, General, U.S. Army (ret.)

(1) He has demonstrated a celerity as student and scholar from which, I confess, I myself should perhaps draw a rueful example.

It has occurred to us (myself and Professor St. John, who represent the small but dedicated curatorial staff of the Bassanda archives-in-exile at Miskatonic University) that, with the advent of the new millennium and its remarkable communications tools—what would Yezget Nasilsinez have been able to accomplish with Web 2.0 and social media: the mind reels!—that the time might be right for a reinvestigation and reinvestment in public advocacy on behalf of the lost world of Bassanda. With the unexpected but very welcome interest shown, across a wide diversity of clienteles, in the activities and possibilities of the Elegant Savages Orchestra—who in exile on the Never-Ending Tour, continue, as you know, under Nasilsinez’s motto “fierce dedication to the traditions, and to one another”—we think that there is a distinct window of opportunity here. Though the massive gaps in the Bassandan historical and archival record resulting from the redactions and cultural reawakenings of the Soviet era can never be entirely filled, it does seem possible that, through the pooling of resources and insights from contributors around the globe, a remarkable amount of data might be collated and disseminated. We envision a “Bassanda Corresponding Society,” admission to which would be on the basis of invitation and special aptitudes, and which, through the magic of the social media which could never have been imagined by the first generation of Bassandan scholars (I am thinking here for example of the c1890s Young Gentleman’s Oriental Society of Talpa), could assist in recovery and new appreciation of our beloved homeland’s culturally and musically diverse riches.

This moment of opportunity as represented by social media and new technology, and by the interest in the ESO, is further enhanced by the presence now, here at Miskatonic, of a remarkably visionary yet practical Dean of Oriental and Musical Studies, who has pledged and demonstrated commitment to artistic inclusivity to a degree that the Professor and I (who remember the bad old days of previous administrations—and as you recall I have been a graduate student here, with the Professor as my supervisor, for nearly three decades) find almost unnervingly positive. In point of fact, that level of support, both financial (modest) and philosophical (vast), and the presence of a pool of enthusiastic students too young to have ever heard, or heard of, Bassandan music, has led the Professor and myself to conclude that we would be remiss in our debt to all that Bassandan culture, and our revered founder Baba Yezget Nasilsinez, gave us, if we were to decline this opportunity.

Colonel Thompson, please do be advised that the Professor and I recognize that your myriad obligations to extended family in the Mountains of New Mexico, and (forgive my mentioning a painful subject) the physical infirmities that have plagued you ever since the War, make it difficult or arduous for you to undertake travel. But we have had communications from Correspondents in Kansas City’s Fair Missouri Command, and from a Buddhist monastery north of you in Colorado, and even from the riverine environment of the Cincinnati river landings, which suggest that all memory of Bassanda is not lost, and that, in a wounded and suffering modern mass-media world, the message of Bassandan musical, cultural, and ethnic inclusivity may resonate more powerfully than ever.

Moreover, though no one could ever have predicted it, the General (B.M., M.M., Oriental and Musical Studies) has proven to be an absolutely exemplary “mature” student since his return to Miskatonic’s ivied halls, yet his tenure here is gradually drawing to a close.[1] We will be very sorry to see him depart, as he has provided such invaluable service to Miskatonic’s department of Musicology, Ethnology, and Cultural Alternatives, but we do feel an obligation as a result to take maximum advantage of his remaining time here.

That being the case, the Professor has directed that I inquire of you on two fronts: first, would your familial obligations and (again, forgive me) physical constraints permit your attendance and participation, in person, at a concert of Bassandan and related music, some time in January of the next year? The General , the Professor, and I all agree that your presence would provide an enormous inspiration and authentication to the young and developing musicians who are the next generation of ESO personnel. We do hope you will take this under consideration.

Secondly, and more immediately: would you believe it might be possible for us here at Miskatonic to take advantage of these new 21st century communications technologies, to author and host a “Bassanda Correspondences” section on the ESO’s website? As you’ll recall, Baba Yezget always believed that both technology, communications, and even modern bureaucratic/administrative structures could, in the right hands, yield personal, humane, imaginative, and creatively inspiring results. And, as I have said, there appears to be a network, largely incommunicado, of Bassanda friends and scholars in locations heretofore unknown or unidentified, with whom contact and collaboration might be initiated.

Do let us know your thoughts.

We remain, Sir,

Most respectfully,

Professor Homer St. John, PhD/LLD, etc., etc

S. Jefferson Winesap (graduate student in music, ethnology, and cultural alternatives)

Miskatonic U

CC: The General, BM/MM, Music and Oriental Studies, General, U.S. Army (ret.)

(1) He has demonstrated a celerity as student and scholar from which, I confess, I myself should perhaps draw a rueful example.

The General weighs in...

Cariños:

It is with abounding pleasure that I read yours of the 2nd inst.

Verily, my heart leaps at the prospect of an impending, if temporary, reunification of the "Bassandan Separatist Front," or, viz., the "Bassandistas." It is my sincerest hope that the price the Reverend Colonel continues to pay for service to his Southron People can be somewhat mitigated* and ameliorated, or, if not then, at the very least, then, indeed, negotiated, so as to permit his travel to these parts, during the first month of the year following.

Please forgive my brevity of response: I simply wanted to express my support for your excellencies' brilliant guidance of this reunion and the proposed use of said Social Communication Tools. At this time the duties of an (elderly) graduate student demand my complete attention.

The concision of this epistle should in no way be taken as commensurate with the esteem and regard in which you are each held, the honor of which is entirely mine.

I will leave you with this epigraph from the Bard:

'"Cry havoc!", and let slip the dogs of war.'

and, finally, this, which the Reverend Colonel will remember from our brief respite in the Land of the Khevsoor:

"Mahdjek, na sahlkhir neem jarood!"

Until we meet again on the Field of Friendship,

I am and remain,

Your brother in arms,

The General, BM/MM, Music and Oriental Studies, General, U.S. Army (ret.)

*([{It has come to my attention that there is a Doctor of Phyzik pursuing his craft in the village of Dixon, in the environs of the Rev. Col.'s Northron New Mexico, who, if the intelligence recd here is to be believed, has made, so the stories tell, great progress in the treatment of such ailments as those plaguing the RevCol, with the use of certain emetics and unguents, the true nature and composition of which he is loathe to reveal. His name is, or that which he goes by, (one can never be entirely sure with these leechmongers), "Julio al Din." I am sure if the RevCol sends one of his lodge brothers to the trading post in Dixon, and has that brother say to the proprietor there, "I am a stranger going to the West to search for that which was lost," he will be taken to meet this "Mr. al Din."})]

It is with abounding pleasure that I read yours of the 2nd inst.

Verily, my heart leaps at the prospect of an impending, if temporary, reunification of the "Bassandan Separatist Front," or, viz., the "Bassandistas." It is my sincerest hope that the price the Reverend Colonel continues to pay for service to his Southron People can be somewhat mitigated* and ameliorated, or, if not then, at the very least, then, indeed, negotiated, so as to permit his travel to these parts, during the first month of the year following.

Please forgive my brevity of response: I simply wanted to express my support for your excellencies' brilliant guidance of this reunion and the proposed use of said Social Communication Tools. At this time the duties of an (elderly) graduate student demand my complete attention.

The concision of this epistle should in no way be taken as commensurate with the esteem and regard in which you are each held, the honor of which is entirely mine.

I will leave you with this epigraph from the Bard:

'"Cry havoc!", and let slip the dogs of war.'

and, finally, this, which the Reverend Colonel will remember from our brief respite in the Land of the Khevsoor:

"Mahdjek, na sahlkhir neem jarood!"

Until we meet again on the Field of Friendship,

I am and remain,

Your brother in arms,

The General, BM/MM, Music and Oriental Studies, General, U.S. Army (ret.)

*([{It has come to my attention that there is a Doctor of Phyzik pursuing his craft in the village of Dixon, in the environs of the Rev. Col.'s Northron New Mexico, who, if the intelligence recd here is to be believed, has made, so the stories tell, great progress in the treatment of such ailments as those plaguing the RevCol, with the use of certain emetics and unguents, the true nature and composition of which he is loathe to reveal. His name is, or that which he goes by, (one can never be entirely sure with these leechmongers), "Julio al Din." I am sure if the RevCol sends one of his lodge brothers to the trading post in Dixon, and has that brother say to the proprietor there, "I am a stranger going to the West to search for that which was lost," he will be taken to meet this "Mr. al Din."})]

From the Colonel

My Dearest Gentlemen:

My joy knows no bounds at the pleasurable prospect of an ongoing correspondence with you all regarding our glorious Old Bassanda. Ah,the homeland... I grow misty at the thoughts of the verdant valleys, the trackless deserts, the snow-capped glory of the mountains; not to mention the bustle and clatter of the brasseries and the damask and silk of the houses of ill repute. And of course, our old comrades long since lost, Goddess rest their souls.

As with The General , my present communications must be brief; for I am off to attend a reunion of the old regiment in Santa Fe, and as waggons are being loaded and beasts draped with harness, I have little time before departure to converse.

Nonetheless, I know with all my heart that we will all gain most heartily from this endeavour; Mssrs. St. John and Winesap at Five Nations down in Mississippi will no doubt unearth untold riches for us with their ongoing researches, and of course we all know the deep and dark archives at Miskatonic have hardly been tapped.

My most grateful thanks and appreciation to the General for his references to Julio al Din; no doubt the good sawbone's concoctions will fully restore me to the best of my humours; my ongoing attempts to maintain my martial abilities have, as you know, led me to study the ancient and arcane ways of the far-eastern sword, and the Nipponese version of consensual reality combined with the shocking skill level of the "young bucks" I must face on the dojo floor leave me in a continuous state of bruised-ness. Al Din's emetics will indeed be welcome.

I will write you again at the first opportunity, fair gentlemen, and until then I of course remain

Your humble and obedient servant

The Rt. Rev. Col. R.E.C. Thompson

My joy knows no bounds at the pleasurable prospect of an ongoing correspondence with you all regarding our glorious Old Bassanda. Ah,the homeland... I grow misty at the thoughts of the verdant valleys, the trackless deserts, the snow-capped glory of the mountains; not to mention the bustle and clatter of the brasseries and the damask and silk of the houses of ill repute. And of course, our old comrades long since lost, Goddess rest their souls.

As with The General , my present communications must be brief; for I am off to attend a reunion of the old regiment in Santa Fe, and as waggons are being loaded and beasts draped with harness, I have little time before departure to converse.

Nonetheless, I know with all my heart that we will all gain most heartily from this endeavour; Mssrs. St. John and Winesap at Five Nations down in Mississippi will no doubt unearth untold riches for us with their ongoing researches, and of course we all know the deep and dark archives at Miskatonic have hardly been tapped.

My most grateful thanks and appreciation to the General for his references to Julio al Din; no doubt the good sawbone's concoctions will fully restore me to the best of my humours; my ongoing attempts to maintain my martial abilities have, as you know, led me to study the ancient and arcane ways of the far-eastern sword, and the Nipponese version of consensual reality combined with the shocking skill level of the "young bucks" I must face on the dojo floor leave me in a continuous state of bruised-ness. Al Din's emetics will indeed be welcome.

I will write you again at the first opportunity, fair gentlemen, and until then I of course remain

Your humble and obedient servant

The Rt. Rev. Col. R.E.C. Thompson

More from the Colonel

S. Jefferson Winesap

Miskatonic University

My Dear Professor:

So fine to receive your latest correspondence! The renewed interest in Old Bassanda, always lurking under the surface of so many academic studies, and obviously getting a jolt from the newest social media, gladdens my soul and quickens my breath. Who would have thought that in this day and age the young folks would take such old geezers as us to heart? Well, you'll be happy to hear that I've caught the fever myself and it's roused me from my normal torpor. I was trolling through a cardboard box, filthy with dust and reeking of mildew, that I excavated from my basement the other day, and to my delight I found one of my favorite childhood relics and another fragment that I think you'll find most amazing. The old magazine I thought I remembered wasn't just a figment of my imagination: there it was, almost crumbling in my hand. Indeed, several pages are missing entirely. I can't remember where I got the thing; I think my father might have used it to line an old cedar chest or something, and when I found it as a boy I claimed it for myself. Funny how we forget things - now that I reread it after all these years I can say with near-certainty that this article might be the wellspring from which my love of all things Bassandan flows. How I longed to reinvent myself in such a way! And the other fragment… my God! The possibilities! Regardless, I think you'll find them both fascinating and pertinent as deep background to the present Bassandan explorations, so I'll stop rambling and copy them in their entirety here:

Miskatonic University

My Dear Professor:

So fine to receive your latest correspondence! The renewed interest in Old Bassanda, always lurking under the surface of so many academic studies, and obviously getting a jolt from the newest social media, gladdens my soul and quickens my breath. Who would have thought that in this day and age the young folks would take such old geezers as us to heart? Well, you'll be happy to hear that I've caught the fever myself and it's roused me from my normal torpor. I was trolling through a cardboard box, filthy with dust and reeking of mildew, that I excavated from my basement the other day, and to my delight I found one of my favorite childhood relics and another fragment that I think you'll find most amazing. The old magazine I thought I remembered wasn't just a figment of my imagination: there it was, almost crumbling in my hand. Indeed, several pages are missing entirely. I can't remember where I got the thing; I think my father might have used it to line an old cedar chest or something, and when I found it as a boy I claimed it for myself. Funny how we forget things - now that I reread it after all these years I can say with near-certainty that this article might be the wellspring from which my love of all things Bassandan flows. How I longed to reinvent myself in such a way! And the other fragment… my God! The possibilities! Regardless, I think you'll find them both fascinating and pertinent as deep background to the present Bassandan explorations, so I'll stop rambling and copy them in their entirety here:

(obscured by a rip) 2, 1947

Taken As A Whole Magazine

American University of Beirut

The Mysterious Never-Ending Journey of Habjar-Lawrence Nasilsinez by (obscured by stains)

One looks back to the great days of Victorian exploration, and names leap to mind with ease: Stanley and Livingstone, Burton and Speke, Franklin. But even the most enthusiastic historians seem to have forgotten one name that, in its day, was on par with the above-listed gallery of immortals: Habjar-Lawrence Nasilsinez.

H.L. Nasilsinez seems to have been born in or near Foyers, Scotland about1845; the repository where birth records were stored for the surrounding area burned to the ground in 1858, thus Nasilsinez's life is a mystery from the very beginning.

Clearly, few Scottish natives are dubbed with the surname Nasilsinez; nor is a Nasilsinez tartan extant (though it is rumored that H.L. Nasilsinez commissioned one during his second and final visit home in the late 1800's. No evidence of the pattern exists). There are Lawrences, however, even though the name is more commonly encountered in England. H.L.'s parents were Angus Gaughan Lawrence, listed in a late-eighteenth-century census as a "lesser gentleman" and Melissa Cocker, about whom little or nothing is known. Family stories say that A.G. liaised with a much younger Melissa, who was probably a maid or cook in the household, and that Melissa was soon dismissed with a generous severance. Shortly thereafter Melissa and her furious sister Gertrude appeared at the door of the estate with babe-in-arms: the infant Habjar-Lawrence Nasilsinez.

Habjar's given Christian name at birth was lost in the flames along with the records thereof, but again family tradition claims he was always called "Boobles" as a child. (Habjar's highly public eccentricities and behavior as a young man suggest he did all he could to obscure his "true" name in favor of his self-adopted one. As he was about thirteen when the birth-records fire happened, it is even possible that in one of his more delinquent phases he set the fire.)

Angus, overcome with guilt at turning Melissa out while with child, took her back in and claimed young Habjar as ward, giving him the family name, to the deep resentment of Lady Lawrence. But only months after her return to Foyers, Melissa was struck low by a vicious hemorrhage and died shortly thereafter. Habjar was raised by his aunt Gertrude and Angus, and never knew his birth mother. Lady Lawrence hated the child and refused to have anything to do with him, banishing him to the servant's quarters with his aunt.

The only room in the house where young Habjar was allowed other than the kitchens was his father's extensive library. Reportedly, Habjar could read from a very young age, and was said to have virtually memorized every book in the house by age eleven. He was particularly taken, in a typically Victorian way, with geography and ethnography, and by the time he entered sixth form, he was calling himself Habjar. He claimed he took the name from one of his father's collections of literary exotica, but this has never been verified, and it is certainly possible that it is a pastiche he himself invented. There are some books we can verify Habjar read from the fact that he took them from the library and kept them the rest of his life - guarding them among his most treasured possessions - and those are the complete writings of Captain Sir Richard Francis Burton. It is also certain that Habjar met the great man himself, however briefly; Burton signed two books for his young acolyte: The Book Of The Sword and The Kama Sutra. No doubt, Habjar's proclivities in later life were deeply influenced by these books, as we will see. There is also some evidence that H.L. met Elisha Kane, the great searcher for the lost Franklin, and it is certain that H.L. possessed a fine portrait of Kane. Since Kane died in 1857 when H.L. was only around twelve years old; this claim may be spurious.

Habjar walked out of school in disgust some time around 1861-2, claiming the "…scabrous professors of dung-eating cannot teach me a thing that I cannot better teach myself…" and, against his father's wishes, promptly boarded a steamer for the continent. The young explorer, longing to emulate his hero Burton, headed east as soon as his feet touched the soil of France, and one of his few letters home reports his presence in St. Petersburg in 1864. It is not known exactly where Habjar went on his first journey, but we can must speculate that he penetrated the mountain fastness that was Old Bassanda. All we know for sure is that in 1867 Habjar journeyed home to Scotland - Angus and Lady Lawrence had perished in a train accident, and Habjar inherited the estate at Foyers.

Had the young man not inherited the property and mantle of his father, it is likely that no one would have even noticed him. Young men often dashed off to real or perceived adventure in far-off eastern locales, usually never to be heard from again. But there was money in the family coffers and the local papers took notice of Habjar's return to the fold, and it is thus that we have the first official description of him. He was said to be of bizarre appearance, with long hair and an even longer beard with various beads and trinkets braided into it. He wore a strange hat with a pointed topknot and long, dangling ear-flaps, and a colorful robe said to have "…so many pleats it is impossible to speculate what may hide within other than the young man's person." His shoes were as pointed as his hat, and of a bright, iridescent material that appeared both red and green depending on the angle of the light, and there were two long, curved sabers on his back. In other words, Habjar had adopted what we now call the dress of the Bassandan warrior caste Jianiczari. Habjar stayed in Foyers several months, long enough to turn the great house over to his aunt Gertrude and set up a self-perpetuating account to keep her in comfort the rest of her years, then as they say, "took the money and ran." Once again, he was off to central Asia.

H.L.'s book Warriors, Mystics, Musicians, And Dancers Of High Bassanda and several surviving extant letters to Gertrude attest that Habjar stayed some time in Bassanda on his second trip, and in fact the third of these letters is signed "Habjar-Lawrence Nasilsinez," the first such appellation on record. H.L. mentioned in passing his esoteric, martial, and musical studies in a few letters, but there can be only conjecture about the nature of his new surname. "Nasilsinez" is hardly a rare name in Bassanda, especially in the mountains on the eastern border which is considered the most difficult and mysterious terrain of that country. The postmarks on many of H.L.'s letters are from Vrdunkos, called by many "The Vienna Of Bassanda" owing to its many schools of music and numerous native composers (Denisova, Kostenki, Batumongke, and Tughtu-Kayisi all come to mind).

Eventually, H.L. moved on, ever-eastward, and his aforementioned book - his only volume of travel and adventure - bears the 1874 imprint of a publisher in Irkutsk, when H.L would have been about twenty-nine years of age. The diaries of the disgraced minor royalty HM S. Owsley-Smythe contain the most extensive written notes of Nasilsinez in this period. Owsley-Smythe visited Nasilsinez about 1880-81, and there is some passing commentary that Nasilsinez fought in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-78, as well as mention that H.L. was walking with a cane. Most interesting is Owsley-Smythe's writing about a small boy who "…clung to Habjar's legs like a pet, never wanting to leave his side and hanging on his every word." (Owsley-Smythe expresses mystification that Nasilsinez never introduced the boy by name despite his obvious devotion to the youngster. Old Bassandan etiquette dictates that one never ask a name or refer to a person by name unless it is offered, and apparently Owsley-Smythe abided by that rule. The young man's name and identity remain unknown, nor is there any mention of a woman living in Nasilsinez's household.) There is also a mention of "…that bastard Nasilsinez…" and a passing comment about a dispute over a courtesan and possibly a duel, in a presently-unpublished packet of the papers of Harry Paget Flashman covering the period in 1879 when Flashman was at Rorke's Drift but it is unknown how or why H.L. would have found himself in Africa, or if the reference is even to the same person we find ourselves concerned with.

At this point, Nasilsinez largely drops off the map for many years except for his final visit to the United Kingdom. He returned to Scotland for unknown reasons and stayed almost a year. There is speculation that Gertrude had died and estate matters needed attending, but no death certificate exists. Villagers in Foyers commented that H.L. sulked in the local pubs, drinking heavily and consorting with the musicians until long after-hours, all the time complaining that he couldn't get "home" to the east. The social columns of London newspapers report his presence at various concerts in the city, particularly those smaller, darker venues that catered to patrons of "the exotic." The same columns report a "family reunion" where H.L. allegedly appeared, and it is possible that the "…precocious young man with a proclivity for boast…" that "…fawned over Nasilsinez like a long-lost uncle with prizes in his pockets…" may have been a young T.E. Lawrence, but T.E.'s own extensive writings never mention Nasilsinez.

Official records show that the (Angus) Lawrence great house at Foyers was sold in late1897, and with only a few scant exceptions Nasilsinez disappears forever. Again, the London papers made great hay out of H.L.'s melodramatic departure by private yacht on May 12, 1898, but once Nasilsinez was out of British-controlled waters there are only two more mentions of him whatsoever, and one may not even refer to him. H.L. himself wrote a letter to Le Figaro in Paris in 1902 announcing that he was abandoning Bassanda "…and that milkmaid… that half-shilling whore…" and returning to Irkutsk with "…sword and saz in hand…." This is the final confirmed location or report of Nasilsinez. The sensational American adventurer and author Richard Halliburton wrote in 1920 of "…witnessing with my own eyes the equine and martial prowess of the great warrior-poet-bard Nasilsinez…" but these particular comments are only to be found in Halliburton's private papers, and were never published in any of his books. H.L. would have been nearly 75 years old by this point and unlikely to have been demonstrating any martial prowess at all, and of course it is not certain that Halliburton even penetrated the Bassandan border, or that the Nasilsinez that he claims to have "…watched gallop his horse at full speed while cutting apples from a tree with his saber…" was even the same person, or even exactly where Halliburton was when he witnessed the alleged event.

It is maddening to the modern scholar and reader that copies of Warriors, Mystics, Musicians, And Dancers Of High Bassanda are so difficult to obtain, and further maddening still that the prose is not only stiff and stilted and almost entirely neglects Nasilsinez's artistic and musical explorations or meaningful ethnography of Bassanda. It is largely dedicated to borderline-sensational anecdotes of duels and sexual conquests that H.L. (or his shoddy editors) seemed to think would sell books like his hero Burton's. This was a gross miscalculation, and so few books were sold that it is conjectured that many of the overstock were destroyed or abandoned in a Siberian warehouse. Noted Prague bookseller Vaclav Klusoz sorrowfully claimed that he found a "trove" of water-stained but readable copies in a weatherbeaten granary in Tehran but the owner, speaking in Persian and pidgin French proclaimed them "merde" and refused to sell them, saying his wife used them to stoke the kitchen-fires.

We may never know what became of Habjar-Lawrence Nasilsinez. He seems to have literally ridden into the sunset - or sunrise, considering that he was bound for the east. One can only hope that his daring and imagination have passed to his illustrious offspring, and that his worthy line may continue for the benefit of musicians and warrior-poets the world over.

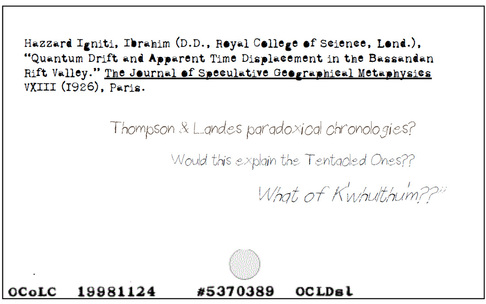

Well. I have no idea if Yezget Nasilsinez ever visited Lebanon (future research for you, my friend? Imagine the revelation if it were confirmed that he met the great Matar Muhammad!) but 1947 seems about right for a possible early tour by a fledgling BNRO… As I said, several pages are missing from my magazine, and even though if the above article were written in conjunction with or in honor of a visit by Y.N. or a tour by the orchestra, a mention thereof might be missing from my copy. Perhaps a duplicate could be found in some archive… and now… an even more tantalizing, and more vague clipping:

* eenville (Greenville?), Mississippi, 18 August 1938

"…liamson, said that one detail of the night stood out other than the conflict that ended Johnson's life - the strange and shadowy presence of a white man in the juke. The man "…was funny-looking…" said Williamson. "He had a pointed mustache and a crazy red hat that looked like an organ-grinder's monkey would wear." Apparently the man was well-dressed and also carried a musical instrument, but Williamson could not identify its type, only that is "…weren't no git-tar like I've ever seen. Had a long skinny neck and a belly like a tater-bug mandolin, and the frets was all messed up."

Other patrons confirm the odd man's presence at the juke but have no comment other than to confirm his unusual dress and that he seemed very interested in the music. One woman said the odd man left before the trouble began. The woman in question, one Mae-Ida Pettigrew, was questioned at her home the day following Johnson's death, but adamantly denied involvement, or the involvement of her boyfriend, Harold "Little Joy" Carter. Carter's current whereabouts are yet to be establ…"

Given that Y.N.'s whereabouts from late 1937-1939 are unknown, I don't have to point out the rather explosive possibilities of this fragment. I think you should put some of your interns on this IMMEDIATELY and see if the complete original can be found, not to mention any further notations of the "odd man" in days subsequent. WOW!

I know the magazine article does little to conclusively add to our knowledge of Yezget's early life, and doesn't even come close to solving what seems to be his greatest biographical mystery - whether he was the son or grandson of Habjar-Lawrence Nasilsinez. Oh well. More digging to do.Well, my friend, I'm off to attempt something productive. God knows how much more I'll find around here… I've got boxes stacked nearly to the ceiling and if I don't expire from hantavirus I'll keep on going through them and who knows what I might find. Until we meet again you of course have my highest regards and I remain

Your humble and obedient servant,

The Rt. Rev. Col. R.E.C. Thompson

I know the magazine article does little to conclusively add to our knowledge of Yezget's early life, and doesn't even come close to solving what seems to be his greatest biographical mystery - whether he was the son or grandson of Habjar-Lawrence Nasilsinez. Oh well. More digging to do.Well, my friend, I'm off to attempt something productive. God knows how much more I'll find around here… I've got boxes stacked nearly to the ceiling and if I don't expire from hantavirus I'll keep on going through them and who knows what I might find. Until we meet again you of course have my highest regards and I remain

Your humble and obedient servant,

The Rt. Rev. Col. R.E.C. Thompson

The following forwarded under separate cover from The General:

Gentlemans,

I am honored Doctor Selim Yakznuroffitov. I work with sad poor skinny childrens in mountains region of beautiful homland of Bassanda (Longz May She Wail!). As you have no doubt hearing on world news broadcasts of televisions we have major serious bigtime probelem of many mountains childrens drinking water from streams in mountains which haz been pissed in by DEGENERATED mountain dwellers INFIDELS and PIG FORNICATORS from UPSTREAM!!!

For to making these situation less shitty more goodness, it is my pleasure and indeed my HONOR to offer to acquaint you with most efficacious and salubrious opportunities for finances advancement by investing in Bassandan National Bank Transfer Accounts. For a one-time fee of $250 paid to the following PayPal account <[email protected]> we will authorizing payment of Bassandan National Bank to yours accountz (be certain to include your bank rauwting numbers and accountz numbers or fee is non-refundable).

Yours in godly working on our times here terrestrially,

Doctor Selim Yakznuroffitov

Chairmen

Bassandan National Piss-in-Water Relief Fundz Bassandan National Governermont Krazdurchillyan, Bassanda 1EZ7 N22O

I am honored Doctor Selim Yakznuroffitov. I work with sad poor skinny childrens in mountains region of beautiful homland of Bassanda (Longz May She Wail!). As you have no doubt hearing on world news broadcasts of televisions we have major serious bigtime probelem of many mountains childrens drinking water from streams in mountains which haz been pissed in by DEGENERATED mountain dwellers INFIDELS and PIG FORNICATORS from UPSTREAM!!!

For to making these situation less shitty more goodness, it is my pleasure and indeed my HONOR to offer to acquaint you with most efficacious and salubrious opportunities for finances advancement by investing in Bassandan National Bank Transfer Accounts. For a one-time fee of $250 paid to the following PayPal account <[email protected]> we will authorizing payment of Bassandan National Bank to yours accountz (be certain to include your bank rauwting numbers and accountz numbers or fee is non-refundable).

Yours in godly working on our times here terrestrially,

Doctor Selim Yakznuroffitov

Chairmen

Bassandan National Piss-in-Water Relief Fundz Bassandan National Governermont Krazdurchillyan, Bassanda 1EZ7 N22O

Dr St John's response:

dEAR WINESAP

PROF ST JOHN HERE. DESPITE THE FACTL THAT i DESPISE ELECTRONIC COMMUNICATIONS – SO MUCH LESS SATISFACTORY THAT CIVILIZED DISCOURSE – i AM TYPING TO YOU ON THIS UNDERGRADUATE PERSON’S “TABLET” TO EXPRESS MY STRONGEST DISAPPROBATION REGADING NEGELCT OF THE ABOVE FORWARDEDD COMMUNICATION YOU WILL WELL RECALL MY STRICT; INSTRUITONS THAT ALL SUCH APPEALS FROM bASSANDAN NATIONALS ARE TO BE TAKEN VERY SERIOUSLY WE HAVE A MORAL OBLIGATION TO USE OU LIMITED FINANCIAL RESOURCES TO HELP THEM!!1 NO DOUBT THE “DEGENERATED MOUNTAIN DWELLERS” RFEENCED IN THE ABOVE ARE THOSE DAMNED xLBITIANS - YOU KNOW THE AGE-OLD CONFLICT BTWEEN bASSANDA ND xLBIT. i EXPECT ACTION ONT HIS HEARTFLET APPEAL FORTHWITH!

sT jOHN

PROF ST JOHN HERE. DESPITE THE FACTL THAT i DESPISE ELECTRONIC COMMUNICATIONS – SO MUCH LESS SATISFACTORY THAT CIVILIZED DISCOURSE – i AM TYPING TO YOU ON THIS UNDERGRADUATE PERSON’S “TABLET” TO EXPRESS MY STRONGEST DISAPPROBATION REGADING NEGELCT OF THE ABOVE FORWARDEDD COMMUNICATION YOU WILL WELL RECALL MY STRICT; INSTRUITONS THAT ALL SUCH APPEALS FROM bASSANDAN NATIONALS ARE TO BE TAKEN VERY SERIOUSLY WE HAVE A MORAL OBLIGATION TO USE OU LIMITED FINANCIAL RESOURCES TO HELP THEM!!1 NO DOUBT THE “DEGENERATED MOUNTAIN DWELLERS” RFEENCED IN THE ABOVE ARE THOSE DAMNED xLBITIANS - YOU KNOW THE AGE-OLD CONFLICT BTWEEN bASSANDA ND xLBIT. i EXPECT ACTION ONT HIS HEARTFLET APPEAL FORTHWITH!

sT jOHN

Winesap replies:

Dear Professor

Yes sir, I do understand and I do recall your very many repeated instructions as regards humanitarian aid from the Institute to Bassandan nationals. However, I must tell you that, in the world of global electronic communications, it is not unheard-of that opportunistic and unethical persons will sometimes impersonate others, especially those in need, in order to run a kind of “confidence game” upon them in order to relieve them of banked funds. Modern communications experts refer to such missives as “spam” and there are electronic safeguards in place to identify and quarantine such communications; that is why you only saw this from “Doctor Yakznuoffitov” in the “spam folder.”

With all respect, Sir, I believe it is appropriate and most desirable that we avoid responding to this confidence trick.

Respectfully,

Winesap

PS: Would you please give me the name of the undergraduate who facilitated you in accessing your email on her or his tablet? I need to have a word with that student.

Yes sir, I do understand and I do recall your very many repeated instructions as regards humanitarian aid from the Institute to Bassandan nationals. However, I must tell you that, in the world of global electronic communications, it is not unheard-of that opportunistic and unethical persons will sometimes impersonate others, especially those in need, in order to run a kind of “confidence game” upon them in order to relieve them of banked funds. Modern communications experts refer to such missives as “spam” and there are electronic safeguards in place to identify and quarantine such communications; that is why you only saw this from “Doctor Yakznuoffitov” in the “spam folder.”

With all respect, Sir, I believe it is appropriate and most desirable that we avoid responding to this confidence trick.

Respectfully,

Winesap

PS: Would you please give me the name of the undergraduate who facilitated you in accessing your email on her or his tablet? I need to have a word with that student.

The Doctor replies:

The Dr responds:

WINESAP:

SPAM? tHE BASSANDANS LOVE SPAM! DONT YOU RECALL THAT IT WAS A CORNERSTONE OF THE HUMANIATIAN AID SENT TO THEM AFTER THE wAR AS PART O THE MARSHALL PLAN, THE bASSANDA LEG OF WHCIH i WAS INOLVED IN SETTING UP?!? I EXPECT ACTION ON THIS FORTHWITH!

sT jOHN

PS; NO IEDA OF UNDERGRADUATES NAME THEY ARE ALL SO YOUNG NOWADAYS

WINESAP:

SPAM? tHE BASSANDANS LOVE SPAM! DONT YOU RECALL THAT IT WAS A CORNERSTONE OF THE HUMANIATIAN AID SENT TO THEM AFTER THE wAR AS PART O THE MARSHALL PLAN, THE bASSANDA LEG OF WHCIH i WAS INOLVED IN SETTING UP?!? I EXPECT ACTION ON THIS FORTHWITH!

sT jOHN

PS; NO IEDA OF UNDERGRADUATES NAME THEY ARE ALL SO YOUNG NOWADAYS

scribbled Winesap note on Archive letterhead:

Colleagues: a moment of incredible excitement and (possibly) earth-shaking significance in the annals of 20th century Bassandan high-art culture--I *may*be on the trail--in the Archive--of primary source material from the legendary, formerly thought to be undocumented premiere of "Xblt Op. 16": the "Bassandan Rite of Spring"! Materials include score sketches; cryptic notes which appear to be for choreography, in a queer and prototypical Laban notation; and fragmented press clippings which suggest that abortive Bassanda premiere may have received nearly as tumultuous a reception as Stravinsky's more famous (and notorious) work! More information when I am able to delve further back into the Archive!

--Winesap

--Winesap

Audio finds in the Archive!

More news: further searches in the Archives have uncovered what appear to be acetate dubs of Radio Free Bassanda shortwave broadcasts, from all periods of the radio era. These materials are in extremely fragile and, in some cases, quite deteriorated condition, but our interns at Bassanda Audio Neurons Group (a/k/a B.A.N.G.) believe that they have the means to resurrect at least a sampling of these archival broadcasts. More information as the reconstruction proceeds.

Typescript from the Archive: unproduced USIA commercial King of the Hill for Bassanda market

....[obscured]...

DALE: "Steering Committee"? That would imply "direction."

DALE: "Hank, I could take care of that Bassandan infestation for ya."

HANK: (deep sigh) ...Dale!..."

BOOMHAUER: "Dang Ol' <mumble> 'Ssandans. Dang Ol' mess."

PEGGY: "Why yes, it just so happens that, as a certified substitute teacher, I AM an authority on Bassanda. Now let me just see if I can find it on this map..."

LOU ANNE: "Unca Haynke, Do Bassandans live in houses?"

BOBBY: "Dayd, kin I join the Bassandan junior folkloric ballet troupe at school?"

HANK: "<deep sigh> ... Bobbeh, someday I will grow old, and I will die... then you kin join the <pause> Bassandan folkloric <pause> ballet <deep sigh>..."

BILL DAUTERIVE: "I have Bassandan on muh momma's side."

COTTON HILL: “Heckfahr, I ‘member them Bassandins! They’iz inna next foxhole ta me on Iwo Jimer. They’z NEAR as tough as a 'Murrikin!"

DALE: "Steering Committee"? That would imply "direction."

DALE: "Hank, I could take care of that Bassandan infestation for ya."

HANK: (deep sigh) ...Dale!..."

BOOMHAUER: "Dang Ol' <mumble> 'Ssandans. Dang Ol' mess."

PEGGY: "Why yes, it just so happens that, as a certified substitute teacher, I AM an authority on Bassanda. Now let me just see if I can find it on this map..."

LOU ANNE: "Unca Haynke, Do Bassandans live in houses?"

BOBBY: "Dayd, kin I join the Bassandan junior folkloric ballet troupe at school?"

HANK: "<deep sigh> ... Bobbeh, someday I will grow old, and I will die... then you kin join the <pause> Bassandan folkloric <pause> ballet <deep sigh>..."

BILL DAUTERIVE: "I have Bassandan on muh momma's side."

COTTON HILL: “Heckfahr, I ‘member them Bassandins! They’iz inna next foxhole ta me on Iwo Jimer. They’z NEAR as tough as a 'Murrikin!"

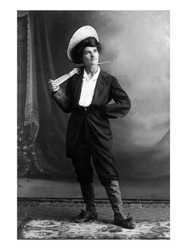

Leon Avventoros Anderson, former OSS / CIA analyst (1947-74); journalist/author/presenter (1968-92) [image: Bassandan coast, c1956]

Deposition (excerpt--redacted under FOIA 2012)

(...)

just

"OK, I’m trying to cast my mind back to the height of those Cold War days—we’re talking almost 60 years ago now, and some of this stuff is awfully foggy. At that time, we all accepted that the mission was to try to understand these places: it was a point of pride for us as analysts that we absolutely resisted pressure from the political establishment to cook the data and give them what they wanted. But Bassanda was tough, because so few of us had been there or knew anyone who had been, and the reports we got were massively conflicted. I guess I got assigned to this task (around 1954? somewhere in there) because my great-grandmother had married into a Bassandan family, even though most of my mother’s side were from Crete and the southern Greek islands. Progiagiá (Ed: “great grandmother”) had that Bassandan longevity thing: she lived until 1942, and we know she was born before 1836, because her name appears on a census roll from Heraklion in that year.

Anyway, I’m digging around for some of the notes I made when I came onto the Eastern Med theatre around 1953. It was kind of a backwater—although Palestine was a mess, Dulles was mostly interested in Indochina and in that total clusterfuck that toppled Massadeq in Iran. Looking back, I’m glad I had the Eastern Med, because those assholes were playing nation-builder elsewhere. They figured, because of my family background, my language skills, and the fact that I was interested in folklore and ethnology and music, I might be able to get on with the Bassandan contacts, because those were the same things the contacts cared about.

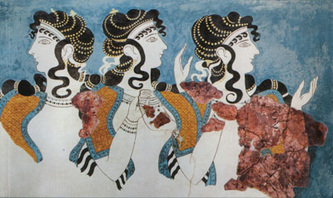

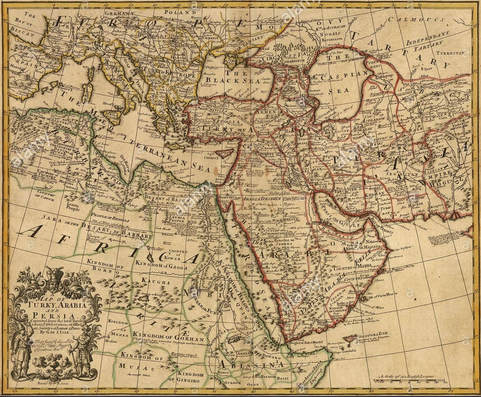

What we knew at the time was that, because Bassanda had a relatively small square mileage, with few natural resources like precious metals, spices, minerals, or oil, it had never been a principal target for imperial conquest. On the other hand, its location meant that it had been an imperial transit zone a la Afghanistan: everyone from Alexander to Suleiman to Peter the Great to Nicholas I had tried to annex the region so as to control access, and usually gotten their asses kicked in the process. Because its landscape was so fierce—for a country with small square mileage, they managed to pack in high-altitude steppes, old-growth alpine forests, mountains, rocky seacoast—nobody was really interested in colonizing there either. And the locals had been a tremendous headache for any outsiders with imperial ambitions: they had that tribal loyalty thing going, they absolutely hated to be told what to do, they had this oral tradition of epic poetry that went back at least 2000 years, and they prided themselves on their skills as horsemen and sailors. So sometimes they fought as mercenaries for surrounding states, sometimes they showed up in ships’ crews in the Med, the Black Sea, or even into the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean, but mostly they stayed home, farmed, fought, and smuggled. Lot of subsistence farming, some pastoral stuff on the high steppes. They had an incredible sense of their own history, a lot of which was carried in epic poetry—I had learned scraps of old Bassandan from my great-granny, and my grandfather loved to sing his mother’s songs.

The Czars were always interested in controlling Bassanda, just as they were with all the border states on the fringes of the Empire, especially those with any kind of access to warm-water ports. That’s why they meddled in India (well, that and the incredible wealth that Britain took out of there all the way up to 1949), that’s why they tried to horn in on Tibet and Nepal, and that’s especially why they kept locking horns with the Turks. Ivan the Terrible tried to go into Bassanda in the 1570s and it’s one of the only places he decided just wasn’t worth the cost of conquest. That’s not to say that later, dumber Czars didn’t try the same thing: Peter the Great was smart enough to stay out, but Catherine tried to go in in the 1720s and they got the shit kicked out of them again. The Bassandans rejected Czarist “civilization,” though they developed a taste for rifled muskets and vodka that they looted from the pack trains of Imperial troops. Also liked Imperial-issue boots—you could usually tell who had knocked over a pack train by how many barefoot Russian corpses were left behind. It got so bad that the Imperial Cossacks refused to serve there: they didn’t like that their horses were no good in the high mountains, and they hated sailboats, and they were scared shitless of those Bassandan wolfhounds—anyway those were the reasons given by the Cossacks for making themselves scarce.

As was the case in a lot of the satellites, the Bassandans actually welcomed the fall of Nicholas II in March 1917; like those other states, they figured that a progressive, socialist, representative government was preferable to the Czarist bullshit. And they weren’t totally wrong: some people don’t realize just how politically and artistically and socially progressive the Lenin government was, in that brief period between the October Revolution and Stalin’s accession in ’24, but there was great interest in maintaining and celebrating ethnic and artistic diversity. Bassanda actually welcomed Leninist “liberalism”—that was before the CHEKA got going.

When Stalin came in, the Bassandan Soviet Socialist Republic experienced the same kind of social and economic constriction, programs of cultural standardization, Socialist-Realist dictates regarding "appropriate" state arts, and oppression of ethnic or cultural minorities. Pretty much everything both economic and artistic was subsumed under the heading of “progress,” and anything that deviated from the norms and means established for testing progress was regarded as decadent and “anti-proletarian.” For the arts, especially in an ethnic minority republic like Bassanda, this peaked with the repression and show trials of the late 1940s and early ‘50s.

After ’55, there was a gradual, very slow liberalization under Kruschev. Throughout this period there would have been fierce, essentially tribal resistance by geographically and topographically isolated groups, "never fully Russianized". I mean, there are some of those deep valleys, at the head of the coast’s fjords, where nobody ever learned to speak Russian and the census commissars didn’t dare go—because when they did, sometimes their motorcycles came tumbling back down the hillsides with headless corpses tied on them.

I wouldn’t have really grasped everything that Yezget Nas1lsinez was involved in; by the time the Agency became aware of him, around ’47, he was already corresponding with George Orwell but he was also pulling away from the Central Committee. And, in the context of the time, that made him some kind of a good anti-Communist (Orwell published 1984 in 1949). And we knew that he had been involved with organizing anti-Nazi partisans during the War. Beyond that, we just knew that the Bassanda National Radio Orchestra was heavily involved in broadcasts by the BSSR networks. But he always seemed to be a guy you could do business with—smart as hell, and capable, especially in official correspondence with USIA, of conveying that he knew a lot more, and could get a lot more done, than he was willing to spell out. I always had a surmise that his primary loyalty was to “old” Bassanda, the kind of regional and musical diversity that had been in place before the Soviets ever went in. Maybe it was an intuition—my Bassandan great-granny’s instincts for recognizing a countryman and an ally.

Anyway, when I was editing various journalistic fronts for the Agency, in the late ‘50s and early ‘60s, I always tried to make sure the BNRO got a fair hearing. And I would have been absolutely deluged with requests from US and NATO-pact agencies, presenters, and musicians for chances to interact with Nas1lsinez and his orchestra: I don’t know how these folks heard the BNRO’s music, but they seemed to have an incredible amount of information about what Yezget-Bey was doing and they wanted to meet and work with him—in a lot of ways, the Western artists and musicians realized the power of art and music to dismantle Stalinism long before we analysts did. I think some of those westerners were sneaking into Bassanda when they could, because they were so interested in the regional musical cultures.

I guess I can admit this now...I was always kind of more sympathetic to Nas1lsinez and his orchestra and to Bassandan artists & musicians than the Agency might have wanted me to be. I saw how deeply rooted they were in love of country, but the way they managed to love their country and their country’s arts, without getting sucked into that whole Cold War paranoid flag-waving covert bullshit act, and I wished my own Agency and my own supervisors had paid attention to what the arts could tell us and the bridges they could build. When Yezget-Bey got into it with the Bassandan authorities in ’62 during the Missile Crisis, and again ’68 in Prague, I basically told my opposite number in the KGB, through back-channels, that if they snatched Nas1lsinez into the Gulag I would burn every single Soviet agent in the West I knew of--and I knew a lot them. I like to think that I had a little something to do with the fact that he was able to keep recording and touring, even when money got really tight during Brezhnev.