ESO Incarnations & Personnel

The 1948-49 Berlin Air Lift Noir Band

The 1942 CASABLANCA Band

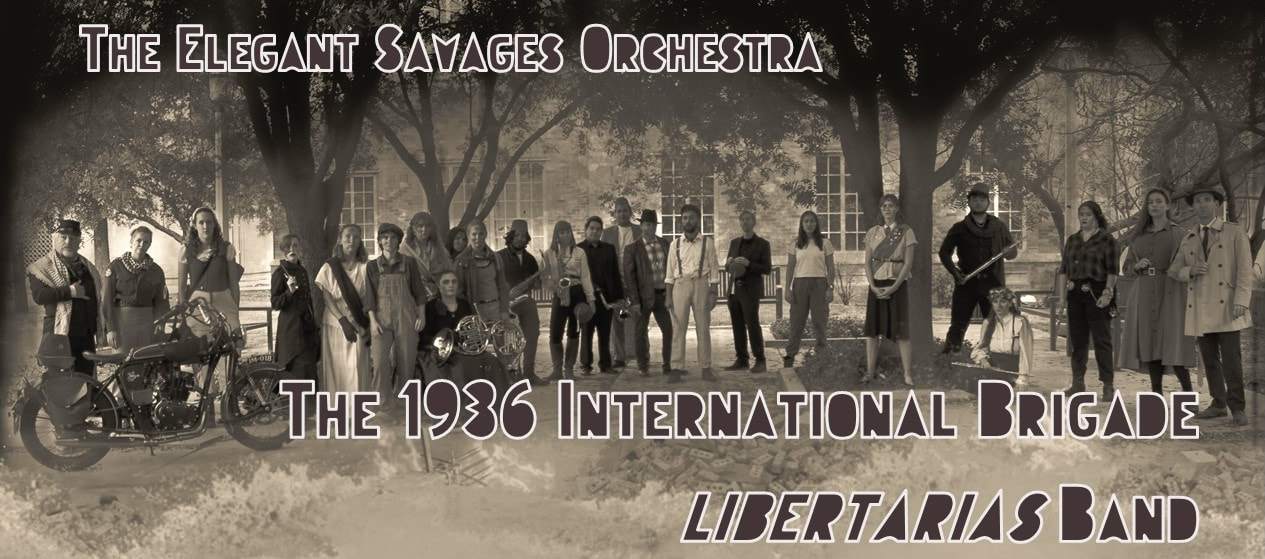

The 1936 International Brigade Libertarias Band

The c1934 Intergalactic Pandemic Popular Front Band

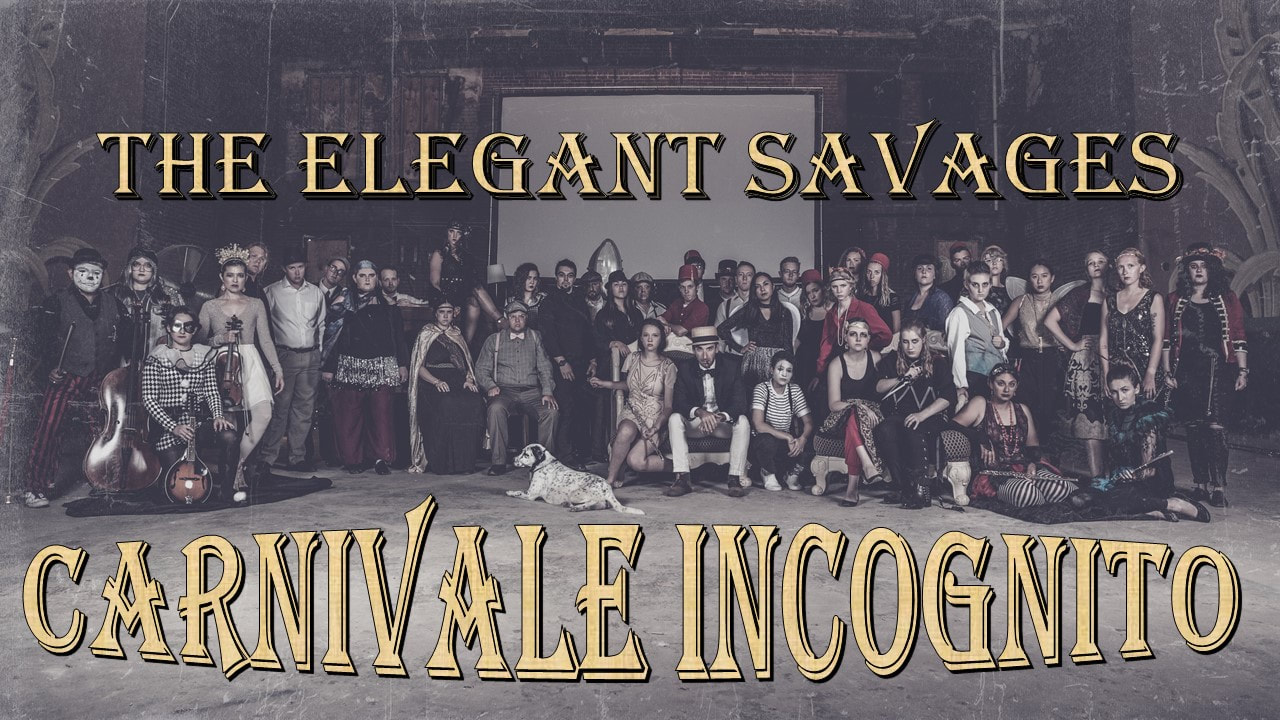

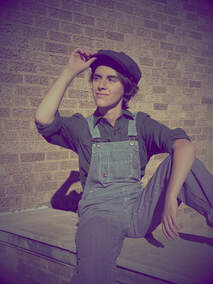

The 1928 "Carnivale Incognito" Band - out Yonder

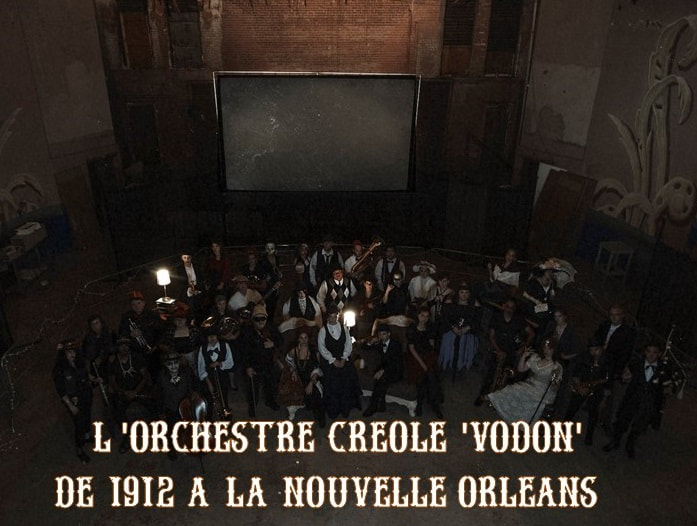

The 1912 New Orleans Creole / 'Vodun' Band

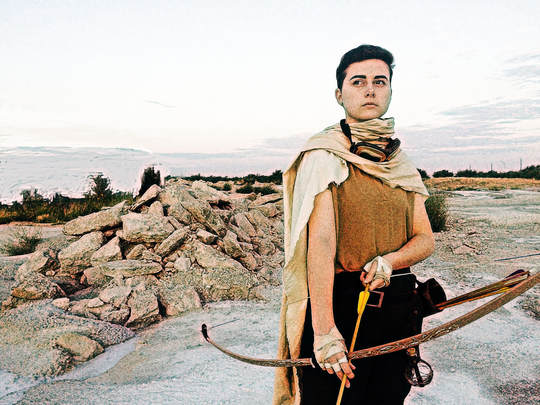

The Great Southwestern Desert

post-Apocalyptic 'Sand Pirates' Band

The Mysterious 1885 Victorian "Steampunk" Band

The 1965 "Newport Folk Festival Band"

The '62 "Beatnik" Band, photographed backstage, Tallinn, c early June 1962.

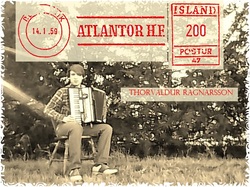

(L-R) foreground: Federica Rozkhov, JDW, Thorvaldur Ragnarsson, Žaklin Paulu (seated);

second row: SMK, Chaya Malirolink, Terésa-Marie Szabo (with Baby Szabo), Ceridwen Moira Ifans,

Морган Ŭitmena, Antanas Kvainauškas, Kaciaryna Ŭitmena, Sian Isobel Seaforth MacKenzie

third row (seated): NS, Nirbhay Jamīnasvāmī

fourth row (rear): “Részeg Vagyok”, AA, Mississippi Stokes, Etxaberri le Gwo,

Raakeli Eldarnen, Jakov Redžinald,

Dzejms Rasel Srcetovredi, Yannoula Periplanó̱menos, Séamus Mac Padraig O Laoghaire,

JE, Binyamin Biraz Ouiz, Fionnuala Nic Aindriú

second row: SMK, Chaya Malirolink, Terésa-Marie Szabo (with Baby Szabo), Ceridwen Moira Ifans,

Морган Ŭitmena, Antanas Kvainauškas, Kaciaryna Ŭitmena, Sian Isobel Seaforth MacKenzie

third row (seated): NS, Nirbhay Jamīnasvāmī

fourth row (rear): “Részeg Vagyok”, AA, Mississippi Stokes, Etxaberri le Gwo,

Raakeli Eldarnen, Jakov Redžinald,

Dzejms Rasel Srcetovredi, Yannoula Periplanó̱menos, Séamus Mac Padraig O Laoghaire,

JE, Binyamin Biraz Ouiz, Fionnuala Nic Aindriú

The "Classic '52 Band"

Rationale: The power of personal myth